The 1995 ‘Trial of the Century’ is back: But so what?

When the cable miniseries meets recent history, distortion is predictable.

So it is with the FX network’s much-ballyhooed dramatization of the sensational O.J. Simpson double murder case, which was tried in Los Angeles in 1995. The proceedings were known extravagantly as the “Trial of the Century.”

The first installment of a 10-part miniseries, “The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story,” aired last night and despite an impressive if all-so-earnest cast, the show hewed to the still-familiar contours of the case. (After all, the miniseries is based on Jeffrey Toobin’s 1996 book about the case, The Run of His Life.)

Lurking powerfully as the debut unfolded were inevitable questions that went mostly unaddressed: So what? Why now revisit the Simpson case?

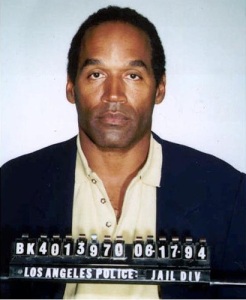

Simpson’s booking photo, 1994

It’s not as if the case is all that urgent or compelling these days, not when most Americans, white and black, now believe Simpson — former professional football star, celebrity, and so-so movie actor — killed his former wife, Nicole, and her friend, Ronald Goldman, in a brutal knife attack outside her condominium in west Los Angeles in June 1994.

Simpson was acquitted, inevitably in my view, of murder charges in early October 1995. The verdicts were greeted jubilantly by many blacks and with head-shaking dismay by many whites.

Even so, the popular verdict quickly emerged in 1995 that Simpson was guilty — a verdict that has hardened with the passing of 20 years and with Simpson’s imprisonment in 2008 on kidnapping and armed robbery charges. So the FX treatment seemed more than a little beside the point: So what? indeed.

Supposedly, the FX miniseries allows us to “connect the dots” between racially charged encounters of the 1990s to those of more recent times.

Maybe.

But as I point out in my latest book, 1995: The Year the Future Began, “the anomalous character of the Simpson trial made it a weak case from which to generalize about a topic as thorny, complex, and multidimensional as race relations in the United States. A single, uncharacteristic case that centered around a single, wealthy defendant who before his trial was little invested in issues and controversies of race simply could not have transmitted a widely applicable message about the state of race relations in America.”

I also note in 1995 that “to argue that the Simpson case did offer a singularly revealing assessment about race in America in the mid-1990s is to ignore other dynamics of the time — in particular, the deepening popular appeal of Colin Powell, the black former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and a hero of the 1990-91 Gulf War with Iraq. In 1995, Powell emerged as a strong prospective Republican candidate for president.”

As Simpson’s prolonged trial neared its bitter end in the fall of 1995, Powell was hailed as the “most popular American of any color.”

How, then, does one square the undeniable appeal of Colin Powell with the notion that the Simpson case exposed deep racial divisions in America? An obvious answer, I argue in 1995, “was that the Simpson case was not all-revealing about race in America in 1995, that it was a misleading or imprecise metaphor.” A misguided parable.

The case was sui generis: The trial dragged on for months and, unlike most murder defendants, Simpson could tap a fortune by which to line up a high-powered defense team.

I write in 1995 that to “evaluate the Simpson verdicts of 1995 principally through a lens of race relations is to discount what perhaps was the most decisive factor in the case — Simpson’s multimillion dollar wealth which allowed his cadre of defense lawyers to even out the adversarial relationship with the state. Simpson’s wealth allowed him to put on a defense of the likes that few murder defendants could ever hope to mount. The aggressive, confrontational strategy his lawyers developed may not have been lofty or inspired. But it was devastatingly effective. Without Simpson’s wealth, that strategy would have remained theoretical.”

Many (though not all) previews of the miniseries gushed about the quality of the cast.

Many (though not all) previews of the miniseries gushed about the quality of the cast.

The cast is fine, but the acting seemed much too earnest, as if the characters were intent on keeping the show from slipping into farce. And all the earnestness produced more than a few moments of eye-rolling.

Sarah Paulson’s unconvincing portrayal of lead prosecutor Marsha Clark as shrill, snappish, and perpetually stressed-out led to a good deal of eye-rolling.

So, too, did David Schwimmer’s portrayal of Simpson’s eager and befuddled friend, Robert Kardashian. Schwimmer, the Ross Geller character of the popular 1990s sitcom series “Friends,” was way too obsequious.

Simpson’s layabout houseguest, Kato Kaelin, is played by Billy Magnussen as an inarticulate airhead.

Simpson is played by Cuba Gooding Jr., who comes across as manic, foul-tempered, and charmless: Hardly the engaging celebrity that once was Simpson’s public image. Gooding also looks a good deal older than Simpson did in the mid-1990s.

The most entertaining performance of the debut was delivered by John Travolta as a stiff, uptight, and devious Robert Shapiro, Simpson’s lead lawyer early in the case. Before the trial, though, Shapiro was replaced by the savvy Johnnie Cochran, who is played, searingly, by Courtney B. Vance.

But the Cochran character inspired a few eye-rolls, too, when he contemplated the color of a suit to wear to an appointment with the singer Michael Jackson.

The FX miniseries is not the only treatment of the Simpson murder case set to air this year: ESPN’s “30 for 30” series is to planning a five-part look back at the case to be shown later in June — confirming anew the long reach of the watershed year 1995.

More from The 1995 Blog:

- The inevitability of O.J. Simpson’s acquittal in 1995

- DNA: The enduring legacy of the 1995 O.J. trial

- Beyond impeachment: The penalties Bill Clinton paid

- Clinton, his portrait, and the persistent shadow of scandal

- Bob Dole, Hollywood, and ‘mainstreaming of deviancy,’ 1995

- 20 years on: Remembering the senator who quit in disgrace

- Terror in the heartland: Oklahoma City, April 1995

- Media fail: A 1995 subtext that’s familiar today

- Why 1995

Pingback: FX miniseries on 1995 O.J. case is crassly exploitative | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Ballyhoo over FX series leads to outsize claims about ’90s O.J. murder case | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Fascination with sideshow: O.J. miniseries mirrors the 1995 trial | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Beyond 1995: Accounting for the pop culture allure of the O.J. case | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: O.J. case ‘do over’: Why the ’95 trial is alive in popular consciousness | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Misportrayals and missing DNA: Closing observations about flawed O.J. miniseries | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Quote of the 1990s? ‘If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit,’ 25 years on | The 1995 Blog