The 1995 Blog turns five: A look back at five top posts

The 1995 Blog was launched five years ago today, in the run-up to publication of my book, 1995: The Year the Future Began. The blog has served to promote the work and to call attention to the ways in which the decisive year of 1995 reverberates these days.

Lasting significance, after all, defines the importance of any year.

And 1995 was made memorable by watershed moments in new media, domestic terrorism, crime and justice, political scandal, and international diplomacy. Not surprisingly, its effects have been felt for years.

The blog’s fifth anniversary is a fitting occasion to revisit its top posts — essays that addressed the sweep and rich variety of 1995 while underscoring just how pivotal the year was.

Lasting significance? It’s a hallmark of 1995.

It was a transcendental year when the Internet and the World Wide Web reached something of a critical mass and entered mainstream consciousness. Amazon.com opened for business online in July 1995, selling books. Within years, Amazon had demonstrated that it was disruptive force unlike any in the digital world.

It was the year of the “Trial of the Century,” when O.J. Simpson answered in criminal court to charges he viciously stabbed to death his former wife and her friend. Simpson was acquitted and remains a fixture in popular culture, if only because of his utter shamelessness and the perverse fascination about how he beat the murder charges.

The rise of the Internet and the “Trial of the Century” are two topics that The 1995 Blog has addressed several times over the past five years. Another recurring theme is the sex-and-lies scandal that nearly cost Bill Clinton his presidency and damaged his reputation even among Democrats.

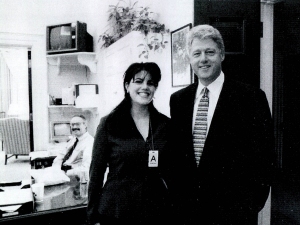

Sex and lies: Clinton with Lewinsky

Clinton’s dalliance with Monica Lewinsky, then a White House intern, began in mid-November 1995 and continued intermittently until March 1997. The affair exploded into scandal in January 1998 and led to Clinton’s impeachment late that year on separate counts of perjury and obstruction of justice.

He escaped conviction during trial before the U.S. Senate in early 1999. But the effects of the scandal have lingered, helping to fuel the fierce and bitter partisanship that defines contemporary U.S. politics. And yet, important details related to the falsehoods Clinton told under oath during the impeachment saga tend to be overlooked, or dismissed, as the top 1995 Blog post of the past five years emphasized.

Here is a rundown about that and four other prominent essays posted at The 1995 Blog over the past five years:

■ Beyond impeachment: The penalties Bill Clinton paid (posted January 19, 2016): As I noted in 1995, Clinton may have “succeeded in beating back the impeachment charges, but his mendacity did not go unpunished.”

Two months after his acquittal by the Senate, Clinton was found in contempt of court by Susan Webber Wright, the federal judge who presided at the deposition Clinton gave in January 1998 in a sexual harassment lawsuit brought by Paula Jones, an Arkansas state employee when Clinton was the state’s governor. Jones claimed he propositioned her at a hotel room in Little Rock in 1991. At the deposition, lawyers for Jones asked Clinton about his intimate affair with Lewinsky, questions he attempted to dodge.

In her finding of contempt of court, Judge Wright said in a scalding opinion that the “record demonstrates by clear and convincing evidence” that Clinton under oath gave “false, misleading and evasive answers that were designed to obstruct the judicial process.”

Simply stated, the judge wrote, Clinton’s “deposition testimony regarding whether he had ever been alone with Ms. Lewinsky was intentionally false, and his statements regarding whether he had ever engaged in sexual relations with Ms. Lewinsky likewise were intentionally false ….”

She imposed an unprecedented if little-recalled penalty, finding him in contempt and ordering him to pay nearly $90,000 to cover legal fees and other expenses that Jones’s lawyers incurred “as a result of the falsehoods he told under oath.”

On the last full day of his presidency in 2001, Clinton acknowledged he had testified falsely at the deposition in 1998 and surrendered for five years his license to practice law in Arkansas, his home state. He also agreed to pay a $25,000 fine to the Arkansas Bar Association.

It’s quite likely that the spectacle and drama of Clinton’s impeachment never would have happened if not for the brief, partial closure of the federal government in November 1995. The shutdown was the upshot of a spending dispute between the Clinton administration and Republican-controlled Congress, and resulted in the furlough of 800,000 government employees.

Clinton, Lewinsky in mid-November 1995

At the White House, unpaid interns kept working. Among them was Lewinsky, then 22-years-old. Suddenly, she was working in proximity to the president and their affair — consensual, but dramatically lopsided in terms of power dynamics — began on November 15, 1995. The reckoning for Clinton’s misconduct continues, years afterward.

■ Recalling the ‘coolness’ of the early Web (posted July 16, 2014): Mild debate occasionally flares about how best to think of the Web when it was new. What was it really like in the mid-1990s, when Internet-awareness became reality? Sometimes the early Web is characterized as a primitive and mostly empty outpost of cyberspace. The “Jurassic Web,” as Farhad Manjoo called it 10 years ago.

That’s a facile and short-sighted characterization. The 1995 Blog is far more inclined to regard the early Web as a frontier, a place of seemingly infinite and unfolding possibility. To smirk at what we know now were its shortcomings and primitive character “is to miss the dynamism and to overlook the extraordinary developments that took place online in 1995,” as I note in the book.

Indeed, I further wrote, 1995 was the year “when the Internet and the World Wide Web moved from the obscure realm of technophiles and academic researchers to become a household word, the year when the Web went from vague and distant curiosity to a phenomenon that would change the way people work, shop, learn, communicate, and interact.”

Cool sites, mid-1990s (Atlantic)

The Atlantic brought another dimension to the mild debate, recalling in an essay published five years ago “the tremendous effort devoted to curating, sharing, and circulating the coolness of the World Wide Web” of the mid-1990s. The Atlantic essay, which inspired one of the first posts at The 1995 Blog, pointed out that the “early web was simply teeming with declarations of cool: Cool Sites of the Day, the Night, the Week, the Year; Cool Surf Spots; Cool Picks; Way Cool Websites; Project Cool Sightings.”

That insistent “coolness” was an important indicator of the dynamism of the early Web and spirit of innovation it fostered.

Several prominent mainstays of the online world trace their origins to 1995. Amazon was one of them. So, too, was Match.com. Craigslist began in 1995, first as a free email listing for jobs and apartments in San Francisco. The predecessor to the online auction site eBay was launched in 1995.

And the rousing success in August 1995 of the market debut of Netscape Communication, maker of the first widely popular Web browser, illuminated the World Wide Web for millions of people. Netscape’s initial public offering of shares thrust the Web squarely into popular consciousness unlike any other event of the 1990s.

■ 20 years after its launch, Amazon showing an unlikable side (posted July 14, 2015): The year 1995 gave rise to no more impressive commercial success story than that of Amazon.com. From its obscure launch in mid-July 1995, Amazon has become the world’s largest online retailer and a dominant force in Internet cloud storage and computing services.

But its growth to multibillion dollar global company inevitably has stoked worries that Amazon has become too big, too pushy, and too intrusive.

Such concerns were raised at The 1995 Blog in a post coinciding with the 20th anniversary. The essay pointed to Amazon’s ugly side, a feature that has become more apparent in the years since.

The blog post described Amazon as “a not especially friendly company” and one “that projects an air of arrogance and distance,” despite its supposed emphasis on attentive customer service. The post noted that “gushing” has become more common media reports about the company and its founder, Jeff Bezos, now the world’s richest person.

Amazon can be a bully, as it demonstrated in a dust-up a few years ago with publishers and authors. Its bullying was apparent again in seeking tax and other incentives from cities and states eager to land Amazon’s second headquarters; when officials in New York City raised objections about the handouts proposed for Amazon, Amazon backed out. The incentives were little more than giveaways to a very rich company that also is known to treat its warehouse employees poorly.

And Amazon finds ways to avoid paying much in federal taxes.

Amazon’s unlikable side, evident five years ago, has only become more prominent.

McVeigh in custody

■ ‘Othering’ and the 1995 OKC bombing: Wiping away McVeigh? (posted April 27, 2018): It is curious that the site of the country’s deadliest encounter with domestic terrorism is without specific reference to the terrorist who brought wanton destruction to America’s heartland early on Spring day in 1995.

The terrorist, a disgruntled Army veteran named Timothy J. McVeigh, packed a Ryder rental truck with explosives — fertilizer and a high-octane racing fuel, inside 55 gallon drums — and without warning blew up the Alfred P. Murrah federal building in Oklahoma City just after 9 a.m. on April 19, 1995. In all, 168 people were killed and hundreds more were injured.

Among the fatalities were 15 children at a day care center on the building’s second floor.

A contemplative site

The site has been transformed into a meditative outdoor memorial that features a shallow reflecting pool guarded by loblolly pines, and 168 bronze-and-glass chairs, each commemorating a fatal victim of McVeigh’s attack. The site, I wrote in 1995, is “a soothing, well-manicured place that seems almost pastoral, an anomaly in a city. It is hard to believe that the parklike memorial was ground zero for an attack of deadly terror.”

I further noted that for “all its ingenuity and quiet appeal, the outdoor memorial is somehow anodyne. There are few obvious or specific references to the havoc and horror of the attack. … There is nothing explicit about the perfidy” of McVeigh who, I added, “is neither demonized nor condemned — just improbably absent and ignored.”

Park Service rangers who give interpretative talks there typically do not mention McVeigh, almost as if uttering his name would demean the site.

That sense was deepened last year as I watched online video of the outdoor remembrance ceremony at what was the Murrah building. The only allusion to McVeigh and his two accomplices (neither of whom was with him in Oklahoma City on April 19, 1995) was indirect, and came in a prayer read by a retired Oklahoma City police chaplain.

In a post a few days later, I noted that ignoring McVeigh or refraining “from mentioning his name when relevant to do so hints at a phenomenon that Kenneth Foote, head of the geography department at the University of Connecticut, has called the ‘othering‘ of violence.” That is, Foote wrote in a scholarly journal article in 2016, an inclination “to label or characterize the killing in ways that distance the killer from the community and have the effect of positioning the violence outside social norms.” (Emphasis added.)

This is not at all to say that there should be public memorials to the mass killer of Oklahoma City. But Foote’s characterization of “othering” has resonance, I wrote, to the popular understanding of the Oklahoma City attack:

“Distancing ‘the killer from the community’ may well be what is happening. Which is troubling, especially as officials in Oklahoma have been unsettled by the prospect that the bombing is slipping from the consciousness and understanding of a generation too young to remember the attack.”

To ignore the loathsome central figure of the attack and to seldom speak his name, I added, “seems a sure way to aggravate that predicament.”

■ Colin Powell, three electoral votes, and what might have been (posted: December 21, 2016): As O.J. Simpson’s racially fraught “Trial of the Century” was lurching to a verdict in early Fall 1995, a boomlet arose for Colin Powell, a hero of the Gulf War of 1990-91 and prospective Republican candidate for the presidency in 1996.

Powell, an African American who was the high-profile chairman of the Joint Chiefs of State during the war, was characterized in 1995 as the “most popular American of any color.”

The boomlet was tied to publication of Powell’s memoir, which came out in September 1995 to mostly favorable reviews. The book, My American Journey, debuted atop the New York Times best-seller list of October 1, two days before Simpson was acquitted by a jury in Los Angeles.

Powell’s book tour was closely scripted but attracted diverse crowds of admirers — “black and white, old and young, affluent and unemployed,” as the New York Times reported.

Powell’s book tour was closely scripted but attracted diverse crowds of admirers — “black and white, old and young, affluent and unemployed,” as the New York Times reported.

Powell, who had never sought public office, was regarded as a promising possible candidate against Bill Clinton, who at times during his first presidential term seemed adrift and not quite up for the job. The burst of “Powell-mania” in the Fall of 1995, John F. Harris, a Clinton biographer recalled years later, “was driving Clinton to distraction.

“The interest in Powell was an implicit rebuke of the incumbent,” Harris added.

Were he to enter national politics, Powell wrote in his memoir, “it will not be because of high popularity ratings in the polls. . . . And I would certainly not run simply because I saw myself as the ‘Great Black Hope,’ providing a role model for African Americans or a symbol to whites of racism overcome. I would enter only because I had a vision for this country.”

In the end, Powell said he would not seek elected office in 1996, declaring in late 1995 that a run for the presidency was “a calling that I do not yet hear.”

A reminder of Powell’s flirtation in 1995 with a run for the presidency came more than 20 years later, when ballots in the Electoral College were cast in December 2016.

Powell received three electoral votes, cast by faithless electors in Washington state who declined to honor pledges to support Hillary Clinton, the Democratic nominee who carried the state in the general election. Powell’s votes officially placed him third, far behind Clinton and the winner, Donald J. Trump, in the voting that formally elected the president. “It made Powell something of a footnote in the turbulent 2016 presidential election, a race he had not entered,” I noted.

I argued in 1995 that Powell’s popularity and book tour in 1995 were often-overlooked counterpoints to claims that the Simpson trial and verdicts had exposed deep racial divisions in America. How could one square the popularity of Colin Powell with the divisiveness that the Simpson case had brought to the fore?

“An obvious answer,” I wrote, “was that the Simpson case was not all-revealing about race in America in 1995, that it was a misleading anomaly or an imprecise metaphor.”

Other memorable posts at The 1995 Blog:

- Exoplanet discovery a memorable first in 1995

- Recalling Dianne Feinstein’s gracious tribute in 1995 to sex-harasser Bob Packwood

- Recalling the ’95 case against lecherous Bob Packwood, whom Biden praised

- ESPN’s O.J. doc: Less exceptional than its rave reviews

- When the U.S. stood still: Awaiting the O.J. verdicts in 1995

- Clinton, his portrait and the persistent shadow of scandal

- The 1995 caricature that’s ‘become part of shutdown lore’

- The smears Lewinsky ignores

- Spoofing her majesty in the ‘Great Royal Phone Embarrassment’ of 1995

- How important was Netscape?

- Hype and hoopla in a watershed year: Launching Windows 95

- Bob Dole, Hollywood, and ‘mainstreaming of deviancy,’ 1995

- Prediction of the year 1995: Internet ‘will soon go spectacularly supernova’

- Why 1995

Pingback: Nobel Prize: Recognizing the 1995 discovery of the first exoplanet | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: With us still: 1995, 25 years on | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: With us still: 1995, 25 years on | The 1995 Blog