Watershed status of 1995 explored in book rollout at Newseum

Why 1995 merits recognition as a watershed was a central discussion point yesterday at the rollout of my new book, 1995: The Year the Future Began.

Why 1995 merits recognition as a watershed was a central discussion point yesterday at the rollout of my new book, 1995: The Year the Future Began.

The reasons for the year’s watershed status essentially are twofold, I said during a program at the Knight Studio of the Newseum, the museum of news in downtown Washington, DC.

One reason is that 1995 was marked by two distinct “flashbulb moments” — events of such intensity and importance that many people remember where they were when they received the news.

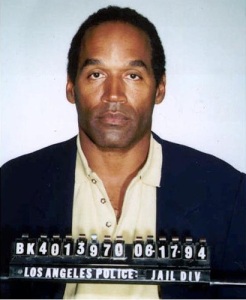

Those moments came in April and October 1995 and, respectively, were the devastating truck-bombing of the federal building in downtown Oklahoma City, in which 168 people were killed, and the not-guilty verdicts in the sensational, months-long O.J. Simpson murder trial in Los Angeles.

The year further merits watershed status because of other significant developments that were less immediately prominent or clear — notably, the emergence of the Internet and World Wide Web into mainstream consciousness, and the partial shutdown of the federal government in November that enabled a 22-year-old intern, Monica Lewinsky, to get close to President Bill Clinton. Their sexual dalliance began the day after the government closure and continued intermittently until 1997 before exploding in scandal in early 1998.

So 1995 was one of those rare years in which its exceptionality was instantly evident in “flashbulb moments” and apparent in the passage of time. In other words, I said, one could sense at the time that 1995 would be recognized as a watershed year and that likelihood was confirmed as the significance of other events and developments revealed themselves over time.

The landmark events of 1995 — the rise of the Internet, the Oklahoma City bombing, the Simpson trial, the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal as well as the U.S.-brokered negotiations that ended the war in Bosnia — are treated as chapters in the 1995 book. And each was discussed in turn at the Newseum program, which was moderated by John Maynard, a former journalist.

The Simpson murder trial received a fair amount of attention during the 45-minute program, which suggests how that case still commands fascination, still exerts a pull.

Simpson, a black former professional football star, was accused of slashing to death his former wife, Nicole, and her friend, Ronald Goldman, outside her condominium in Los Angeles. Both victims were white.

The verdicts, read in court at 10 a.m. Pacific time on October 3, 1995, were widely anticipated in America. The country, I pointed out, nearly ground to a halt as the verdicts were awaited.

Some passengers, I said, refused to board airplanes until they knew the outcome of the case. News conferences on Capitol Hill in Washington were delayed or canceled. Senator Joseph I. Lieberman of Connecticut postponed a news conference that would have coincided with the reading of the verdicts. “Not only would you not be here,” he told reporters, “but I wouldn’t be here, either.”

Reactions to verdicts also attracted much attention, in that many African Americans cheered and celebrated Simpson’s acquittal while many whites were shocked and crestfallen. A questioner in the audience yesterday referred to the disparate reactions to the Simpson verdicts and asked whether they signaled important insights about race in America.

Not in a lasting way, I replied, pointing out how anomalous the Simpson case really was. Most murder cases do not go to trial and rarely do defendants have the resources Simpson had. His multimillion dollar wealth enabled him to recruit a legal team that went toe-to-toe with the prosecution and effectively challenged the best evidence amassed against Simpson — forensic DNA evidence that seemed to point to his guilt.

Simpson’s legal team thoroughly impugned the collection, handling, processing, and analysis of that evidence which, I said, was a major reason Simpson was found not guilty.

I also pointed out that in late summer and early autumn 1995, as the Simpson case was nearing its conclusion, Colin Powell was emerging as a prospective Republican candidate for president.

Powell, also African American, was a retired chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and a hero of the 1990–91 Gulf War with Iraq.

His popularity in 1995 is not often recalled these days. It was sometimes called “Powell-mania,” and it was buoyed then by a nationwide tour to promote his memoir, My American Journey, which came out in September 1995 to mostly admiring reviews. The book debuted atop the New York Times best-seller list on October 1, 1995, just as the Simpson trial was nearing its denouement.

In promoting his book, Powell (who in the end decided against running for president) attracted large and diverse crowds of admirers — “black and white, old and young, affluent and unemployed,” as the Times reported.

So how, I write in 1995: does “one square the popularity of Colin Powell with the view that the Simpson verdicts had exposed deep racial divisions in America? An obvious answer was that the Simpson case was not all-revealing about race in America in 1995, that it was a misleading anomaly or an imprecise metaphor.”

Another question raised during the Newseum program was what other, more recent year or years might be regarded one day as a “watershed”?

I replied that it may be too soon to make such selections with much certainty but added nonetheless that strong candidates appear to be 2001, given the “flashbulb moment” of the deadly terrorist attacks on New York City and the Pentagon, and 2008, year of the election of Barack Obama, the first African American president.

C-SPAN’s Book TV will air the Newseum program at 11 p.m. on January 11.

More from The 1995 blog:

- Media fail: A 1995 subtext that’s familiar today

- Quirkiness on New Year’s Day, 1995: ‘Far Side’ farewell, errant Clinton prediction

- The big gap in Monica Lewinsky’s speech

- So. Africa case like the O.J. Simpson trial in 1995? Only marginally

- Recalling the ’95 case against lecherous Bob Packwood, whom Biden praised

- Hype and hoopla in a watershed year: Launching Windows 95

- Lesson misunderstood: NATO’s 1995 bombing in Bosnia

- Illuminating the Web: Netscape’s IPO of August 1995

- How important was Netscape?

- Recalling the ‘coolness’ of the early Web

- Anniversaries, controversies for Amazon.com

- What did the ’90s mean?

- The ’90s deserve better

- Why 1995?

- Talking 1995

- Welcome to The 1995 blog

Pingback: Going ‘Majic’ for a brisk radio discussion about 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: ‘1995 was watershed moment in consumer technology,’ says Intel CEO | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: What ‘Time’ forgot in its look back to 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Part One: Highlights of ‘1995’ interview with Reason.com | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Part Two: Interview takes up scandal and the ’90s ‘zeitgeist’ | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Dow opening today at record high: Reminiscent of 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: ‘The Internet? Bah!’ Classic off-target essay appeared 20 years ago | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: ‘Calvin and Hobbes’ was best ended in 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Talking Internet history, and 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Media fail: The flawed early coverage of 1995 OKC bombing | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: What ‘Clueless’ at 20 can tell us about exploring the recent past | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Predator drone down — over Bosnia, 20 years ago | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Contrived ballyhoo: Recalling Microsoft’s rollout of Windows 95 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: DNA: The enduring legacy of the 1995 O.J. trial | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: A memorable ‘first’ in 1995: Discovering the exoplanet | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Looking back at a watershed year: 1995 in blog posts | The 1995 Blog