FAQs about 1995

Q: So why is the year 1995 book-worthy?

It was a decisive year, a year defined by watershed moments in new media, domestic terrorism, crime and justice, international diplomacy, and political scandal.

It was a decisive year, a year defined by watershed moments in new media, domestic terrorism, crime and justice, international diplomacy, and political scandal.

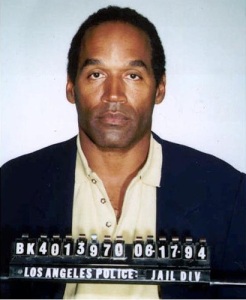

As is discussed in 1995: The Year the Future Began, the year marked the emergence of the Internet into mainstream consciousness. It was the year of the Oklahoma City bombing, an attack that killed 168 people and signaled a deepening national preoccupation with terrorism. It was the year of the double-murder trial of O.J. Simpson, a months-long ordeal often called the “Trial of the Century.” It was the year when a U.S.-brokered peace agreement ended the war in Bosnia, Europe’s most vicious conflict since the time of the Nazis. And it was the year when President Bill Clinton began an intermittent sexual dalliance with Monica Lewinsky, a White House intern 27 years his junior; the affair led to Clinton’s impeachment in 1998.

This is a provocative book that turns a fresh lens on each of those moments. Each was a watershed moment of a watershed year.

Q: What does that mean, “Each was a watershed moment of a watershed year”?

The five major events examined in detail in 1995: The Year the Future Began all were significant. All have exerted lasting influence. All have left an imprint on contemporary life.

Q: Like the rise of the Internet?

Exactly. That’s a very telling, very revealing example. The rise of the Internet, alone, is sufficient to qualify 1995 as a watershed year.

In 1995, the Internet and the World Wide Web reached something of a critical mass. They became household words. Not everyone was online in 1995. But by 1995, almost everyone had at least heard about the Internet and the Web. Everyone seemed to be paying some attention to the Internet. And at the end of the year, Newsweek magazine described 1995 as “the Year of the Internet.” It was a characterization that proved quite apt.

It’s also interesting to note how several mainstays of the online world date their origins to 1995.

Q: Mainstays such as?

Such as Amazon.com, which began selling books online in July 1995 (though not from a garage as is often said).

Other mainstays included the predecessor to eBay, which went online in September 1995. The predecessor to Craigslist.org also began in 1995. Match.com got going in 1995, as well. The Wiki was developed in 1995, opening ways of collaborating online. Yahoo! was incorporated in 1995. The first social-networking site, Classmates.com, was launched in 1995. The founders of Google met in 1995 — on the campus of Stanford University. And at first, they didn’t much like each other.

Those examples demonstrate how 1995 was an innovative and digitally fertile time.

And what illuminated the Web for millions of people in 1995 was the IPO, the initial public offering of shares, of Netscape Communications. Netscape made an immensely popular Web browser and in August 1995, the company went public with an eye-opening IPO, the success of which stunned Wall Street and catalyzed the dot.com boom of the second half of the 1990s. Netscape’s IPO demonstrated that the Web could be a place where fortunes could be made fast.

Moreover, the rapid rise of Netscape — a deeply interesting company that embodied the swagger associated with the early Web — signaled the centrality of the Web in the digital age.

Q: But can 1995 really be thought of as “the Year of the Internet”? Going online was pretty primitive back then, with dial-up modems and such.

By contemporary standards, going online in 1995 certainly was primitive, yes. As Newsweek magazine observed, accessing the Internet in 1995 was like “a journey to a rugged, exotic destination — the pleasures are exquisite, but you need some stamina.” That’s quite a good description.

But to look back to 1995 and scoff at the primitive character of the online experience is to miss the dynamism of the early Web. It was the time when the Internet and Web, in the words of Vinton G. Cerf, one of the fathers of the Internet, went “from near-invisibility to near-ubiquity.”

So 1995 was a decisive time, digitally — the time when the Web was prominently making the transition from vague and distant curiosity to a popular fascination — a phenomenon that would absolutely change the way people work, shop, learn, communicate, and interact.

Q: How was the O.J. Simpson trial a watershed development of a “watershed year”?

It was first high-profile criminal trial in the United States in which evidence about DNA — deoxyribonucleic acid, the distinctive genetic material found in blood, hair, saliva, and elsewhere — was a crucial component. At the Simpson trial, forensic DNA testing was on display as never before. And the most important and lasting contributions of the trial centered around DNA.

The trial stretched across much of the year: It began in January 1995 and ended in early October, with Simpson’s inevitable acquittal. Even though Simpson was found not guilty, the case helped settle disputes about the value and validity of DNA evidence. It also anticipated popular interest in DNA testing, as suggested by the prime-time, CSI-type programs that were developed for television in the years after the Simpson trial.

Q: But wasn’t the Simpson murder trial more meaningful for lessons and insights about race relations in America?

That was a common interpretation during and even well after the trial. Simpson was a black former football star accused of killing his former wife and her friend, both of whom were white. The verdicts produced clashing overt reactions — many white Americans were visibly dejected and disappointed when Simpson’s acquittal was read in court in Los Angeles, and broadcast live across the country. Many African-Americans were jubilant.

The disparate reactions were often interpreted as illuminating a significant, race-based divide in America. But the outcome of the Simpson case neither reversed nor significantly dented a broader trajectory of gradually improving relations among blacks and whites in America. While there have been setbacks from time to time, the trends captured in polling data show increasing racial tolerance among Americans.

The polling data also illuminate sharp differences between white and black Americans in perceptions about the equality of justice in the United States. Differences in perception are crucial to understanding the black-white divide that was seen in the reactions to Simpson’s acquittal. The divide had much to say about perceptions of justice in the United States in the mid-1990s.

At the same time, it is important to recognize what an anomaly the Simpson trial really was. It was quite unlike the vast majority of murder cases in the United States, few of which go to trial. Few murder defendants have the resources to muster the array of legal talent that Simpson recruited to represent him. Multimillion dollar wealth allowed Simpson to put on a defense the likes of which few murder defendants can ever hope to mount.

Because it was such an anomalous case, it is impossible to say that it was very revealing or generalizable about a topic as complex and thorny as race relations in the United States. One journalist wrote that the Simpson trial offered “a distorted example of American justice, in the same way the Playboy Mansion is a distorted sample of American housing.” I think that’s a fair assessment.

Q: You say the acquittals in the Simpson case were “inevitable”: Why?

By the time the case reached the jury, Simpson’s defense team had thoroughly impugned the prosecution’s evidence — including the substantial DNA evidence that pointed to his guilt in the killings.

Interestingly, Simpson’s lawyers did not dispute the science behind forensic DNA testing. Rather, they challenged how that evidence was collected by Los Angeles police. At trial, Simpson’s lawyers extracted acknowledgements from police criminalists that they had mishandled or overlooked DNA evidence.

The shoddy police work allowed Simpson’s defense to raise the far-fetched argument that their client had been framed. Now that was very, very unlikely. But given the series of screw-ups by authorities in gathering, handling, processing, and evaluating the DNA evidence, the claim was at least faintly plausible.

In addition, a police detective prominent in the Simpson case, Mark Fuhrman, was shown during the trial to be a racist and a perjurer. He was a rogue cop — and a godsend to Simpson’s defense team.

By the time the case reached the jury, Simpson’s defense team had so thoroughly challenged the prosecution’s best evidence that acquittal was inevitable, despite his probable guilt.

Q: Do you think it was indeed the “Trial of the Century”?

Probably not. I think it’s more accurate to call it “the most sensational murder trial of the 1990s.”

One of Simpson’s lawyers, Gerald Uelmen, reported there had been more than 30 trials during the Twentieth Century that the news media at one time or another had described as a “trial of the century.” These included the cases of the assassin of President William McKinley in 1901; of Bruno Hauptmann, who in 1935 was convicted in the kidnap-murder of Charles Lindbergh’s infant son, and of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who in 1951 were convicted of spying for the Soviets.

In any event, Simpson’s trial was certainly fascinating, featuring all sorts of plot twists. While he claimed to be eager to testify under oath, Simpson never took the stand in his defense. Even so, he shrewdly drew the spotlight to himself at critical moments during the proceedings. Near the end of the trial, for example, he stood and formally waived his right to testify — and then told the presiding judge, Lance Ito, that he “did not, could not and would not have committed this crime.”

That was a dodgy move that infuriated the lead prosecutor, Marcia Clark. She dared Simpson to take the stand “and we’ll have a discussion.” Simpson didn’t respond. He had made his point, and he did not testify.

Q: So what explains the enduring fascination with the Simpson murder trial?

Fresh interest in the case bloomed in 2016, with a 10-part cable miniseries about the Simpson trial. It was called The People v. O.J. Simpson, and I found it crassly exploitative. And over the top. It offered almost nothing about the decisiveness of DNA evidence at the trial. But there was no denying the miniseries had appeal.

Part of the fascination with the case rests with the perverse but enduring interest as to how Simpson beat a double-murder rap, how he spent millions of dollars on a team of defense lawyers who shredded the prosecution case and won his acquittal, hollow though it was.

Simpson’s narcissism, his crass conduct, and his refusal to buckle at any point in face of the evidence and powerful accusations against him, also explain the resurgent fascination. Simpson’s conduct was repugnant — and flamboyantly so. Right after winning acquittal, Simpson issued a statement read by his eldest son, Jason, in which Simpson pledged to “pursue as my primary goal in life the killer or killers who slaughtered Nicole and Mr. Goldman. They are out there somewhere.”

It was an empty, gratuitous vow that Simpson surely never intended to fulfill.

Q: What fresh interpretations does the 1995 book offer?

It offers many.

The bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City was the deadliest single act of home-grown terrorism in the United States. A disgruntled veteran of the 1991 Gulf War, Timothy McVeigh, was the bomber, and he had help from two Army buddies, Terry Nichols and (to a lesser extent) Michael Fortier. The book rejects as highly improbable the lingering suspicions that the conspiracy was much wider than that.

The book also describes how the Oklahoma City bombing marked the emergence of a more guarded, more suspicious, more security-inclined America. The attack helped to set in place the now-familiar hyper-cautious, security-first mindset that has been accompanied by the imposition of a variety of restrictions aimed at warding off a terrorist attack. The country can be very jumpy about prospective terrorist attacks; that nervousness can be traced to the aftermath of the Oklahoma City bombing.

So that attack was very much a turning point in domestic security and security precautions. It ushered in a regime of restrictions that have become ever-tighter and ever-more pronounced in American life, especially in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001.

Q: What other lasting consequences can be traced to the major events of 1995?

The Clinton-Lewinsky affair, which had its origins during the partial shutdown of the federal government in November 1995, became a full-blown scandal in 1998 that led to Clinton’s impeachment by the U.S. House of Representatives. It was the first time an elected U.S. president had been impeached, which represented an astonishing turn of events.

Clinton was accused of perjury and obstruction of justice, for lying under oath about his relationship with Lewinsky. He was, as anticipated, acquitted at trial before the U.S. Senate, in early 1999. But reminders of the ordeal can be detected today, especially in the cleavages of an often-hostile domestic political environment.

The votes to impeach the president fell largely along party lines: Republicans were mostly in favor; Democrats, mostly opposed. Those votes signaled a sharp partisan divide that has deepened and intensified in the years since, to the point where liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats are rarities in national politics.

It would, of course, be mistaken to attribute contemporary political polarization exclusively to the storms stirred by the scandal and Clinton’s impeachment. But those storms contributed mightily.

And it’s clear that if not for the government shutdown in November 1995, Lewinsky would have lacked the opportunity to get close to Clinton. Most White House staffers were furloughed during the shutdown, which meant the unpaid interns were assigned tasks to help keep the White House running. And that placed some of them close to high-level officials. Lewinsky during the shutdown was assigned to the chief of staff’s office, not far from the Oval Office.

Q: So why did Clinton survive the Lewinsky scandal? Was he just lucky?

Clinton was lucky: He had the consistent good fortune of confronting foes who were inept or who lacked his political wiliness and instincts. In winning the presidency in 1992, Clinton ousted George H.W. Bush, who was perceived to be an out-of-touch incumbent. To win reelection in 1996, Clinton handily defeated a hapless, seventy-three-year-old Republican foe, Bob Dole. During the partial government shutdowns of late 1995, Clinton outmaneuvered Newt Gingrich, the most prominent Republican and the Speaker of the House, to reclaim the momentum in Washington. It’s little-remembered now, but Clinton’s presidency was looking quite beleaguered during much of 1995.

Kenneth Starr, the independent counsel who investigated Clinton’s adulterous affair with Lewinsky, proved to be another of Clinton’s inept foes. Starr was earnest and gentlemanly — but not well-prepared for the furies his investigation unleashed.

Starr’s report to Congress in 1998 that identified grounds for impeaching Clinton was arresting in its graphic detail. Freighting the report with such explicit content proved to be a serious misjudgment — and was another reason why Clinton survived the scandal. In other words, it appeared as if Clinton’s foes were bent on destroying the president amid a welter of explicit and embarrassing detail about his relationship with Lewinsky.

Perhaps more important was that Clinton’s misconduct in the Lewinsky scandal — while reprehensible — fell somewhat short of the standard for impeachment that had been effectively set by Richard Nixon in the Watergate scandal. Clinton’s falsehoods, evasions, and dishonest efforts to conceal his dalliance with Lewinsky hardly rivaled the crimes of Watergate.

And yet, the Clinton sex-and-lies scandal reverberates to this day. Twenty years after his impeachment, Clinton faces a grinding reckoning for carrying on the furtive relationship with Lewinsky. The power dynamics of that relationship were terribly one-sided, and it is likely that Clinton would have been forced to resign the presidency, had the scandal taken place these days.

Q: How do the Dayton peace accords qualify as a watershed of 1995?

The accords — which ended a brutal war that claimed 100,000 lives — were reached in November 1995 after three weeks of intensive negotiations among the leaders of Bosnia, Croatia, and Serbia. The talks were brokered by the United States and convened at Wright-Patterson Air Force base, just outside Dayton, an old factory town half-way round the world from the horrors of the Balkans.

The venue was intriguing and certainly unconventional: The base was sprawling and fairly bristled with reminders of U.S. firepower and military readiness — reminders not lost on the Balkan leaders at the talks.

The negotiations produced a complex and imperfect agreement that essentially divided Bosnia into fairly rigid mini-states: A Croat-Muslim federation and a Serb-dominated republic. It may have been the best outcome achievable after nearly three years of war. The Dayton accords, as they had to, reflected the complexities, the fragility, and the contradictions of the Bosnian state.

But the accords did end the bloodshed in Bosnia. As such they represented a major foreign policy success of Clinton’s presidency.

What’s more, they had the effect of emboldening U.S. foreign policy and the country’s ambitions abroad. It was almost as if the world’s lone superpower was finally hitting stride in 1995 after the Cold War, which had ended with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Bosnia was the first in a succession of ever-more ambitious military operations overseas, which gave rise to what can been called a “hubris bubble” that expanded as military success encouraged even more ambitious undertakings.

The post-Dayton “hubris bubble” burst in the aftermath of the invasion of Iraq. After taking Baghdad and toppling Saddam Hussein’s Baathist regime, the United States was quite unprepared for the bloody insurgency and long war that followed.

The puncturing of the “hubris bubble” did not necessarily foreclose American ambitions abroad. But it led to a decided retrenchment. For years afterward, the United States was reluctant and hesitant to apply force to diplomacy. It was more inclined to lead from behind, as if chastened by the bursting of the “hubris bubble.”

Q: You say the Dayton accords were brokered by the United States. Who was the prime mover?

A colorful American official named Richard Holbrooke.

He was the assistant secretary of state for European and Canadian affairs when Clinton appointed him the point person on a U.S. initiative to end the war in Bosnia. That was in August 1995.

The choice of Holbrooke was more than a little controversial. He was an outsize, colorful, and complex character, who by turns could be charming, abrasive, theatrical, and explosive. Someone once said, accurately, that “hubris” and Holbrooke were inseparable.

He also was given alternately to cajoling, improvisation, and swings of emotion — all of which were on display during the intense negotiations at Dayton, negotiations that often seemed certain to collapse. They really were a fascinating collision of ego, power, veiled threats, arm-twisting, and nights with little sleep for the negotiating teams.

Holbrooke’s cajoling kept the talks going, although near the end he, too, seemed resigned to their failure.

Q: So what happened?

At almost the last possible moment, as the American negotiating team was convening its close-out meeting in fact, the Serbian president, Slobodan Milosevic, proposed a compromise that resolved the final territorial dispute of the talks.

Milosevic was the Balkans leader most eager for a deal at Dayton, which was ironic because he had been most responsible for the years of turmoil and bloodletting in the Balkans following the disintegration of the Yugoslav state. He was a war criminal whose biographers called “the Saddam Hussein of Europe.”

But at Dayton, Milosevic made important concessions and pushed for a negotiated settlement to the Bosnian war, so that the international economic sanctions imposed on Serbia by the United Nations could be lifted, as they were. He also wanted to rehabilitate his international image, but that never happened. Milosevic was indicted in 1999 for crimes against humanity, was turned from power in 2000, was arrested in Belgrade in 2001 and sent to The Hague to stand trial. He died there in a prison cell in 2006.

Q: And what about Holbrooke?

He became U.S. ambassador to the United Nations but never achieved his ambition of serving as secretary of state.

He also spent two mostly unhappy years in the administration of President Barack Obama as a special representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, a post he held at his death in 2010, following emergency surgery in Washington for a torn aorta.

The Dayton accords of 1995 were his major achievement in public life.

Q: If 1995 were such a decisive year, shouldn’t we see evidence that it lives on?

We do have considerable evidence to that effect — how the watershed developments of 1995 live on, how they resonate still.

And how could they not?

The year 1995 was, after all, the time when the Internet entered the mainstream of American life; when terrorism reached deep into the American heartland with devastating effect; when the “Trial of the Century” enthralled and repelled the country and brought forensic DNA to the popular consciousness; when diplomatic success at Dayton gave rise to a period of American muscularity in foreign affairs, when the president and an unpaid White House intern began a furtive and intermittent dalliance that would shake the American government and lead to the extraordinary spectacle of impeachment.

Given those milestones, it is not surprising at all that 1995 extends a long reach.

Take the O.J. Simpson case, for just one example. Not only does the 1995 “Trial of the Century” command popular interest, it remains a standard against which other sensational murder cases have been measured — and inevitably found wanting. No murder trial in the United States since 1995 has matched the Simpson saga for duration, infamy, and unrelenting media attention.

Monica Lewinsky is another example: The former intern is now in her forties and she still compels fascination. She makes it back in the news from time to time. A few years ago, she wrote an essay for Vanity Fair saying that she “deeply regret[s] what happened between me and President Clinton. . . . At the time—at least from my point of view—it was an authentic connection, with emotional intimacy, frequent visits, plans made, phone calls and gifts exchanged. In my early 20s, I was too young to understand the real-life consequences, and too young to see that I would be sacrificed for political expediency.”

That essay was a finalist for a National Magazine Award. It didn’t win. But it signaled her reemergence in public life, and signaled that it will be a long time before the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal is forgotten.

Also, a broader point made in the book about 1995 is that “time has come for a searching reappraisal of the 1990s … to confront and flatten the caricatures so often associated with the decade. The 1990s may still seem recent, but ample time has passed to allow the decade to be examined critically and with detachment.”

There’s good reason for a reappraisal: The 1990s have sometimes been called a “holiday from history,” which is as misleading as it is glib and superficial.

The 1990s were a searching time, rich in promise, in portent, and in disappointment. Located in the midstream of the decade was its most decisive year.

Q: And, finally, what is meant by the book’s subtitle — “the year the future began”?

It means that important features and realities of contemporary life — important to us nowadays — can be traced to 1995.

The fingerprints of that year are all over the present. Another way of thinking of it is that 1995 was when our now began. When our times began.

In 1995, the Internet and World Wide Web entered mainstream consciousness: They became household words. A preoccupation with terrorism, and with measures to thwart the prospect of terrorism, took hold — or certainly intensified — in 1995. The defining character of DNA gained wide recognition in 1995. U.S. foreign policy in the wake of the Cold War took on a hubris and a muscularity, the effects of which we’re still sorting through. And a dalliance between the president and a White House intern began in 1995, an affair that would shake the American government and lead to the spectacle of impeachment.

These all reverberate to this day. So, yes, in very important respects, the future began in 1995. Our “now” began in 1995. Understanding the watershed moments of that vital year can help us better grasp, and unpack, important issues that we wrestle with today.

Pingback: Dow opening today at record high: Reminiscent of 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Clinton, his portrait, and the persistent shadow of scandal | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: ‘Calvin and Hobbes’ was best ended in 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: W. Joseph Campbell and the Watershed Year that Was 1995 | Internet History Podcast

Pingback: Talking Internet history, and 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Terror in the heartland: Oklahoma City, April 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Closing off Pennsylvania Ave.: 1995 and a psychology of fear | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: The crowded closing day of 1995 | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Colin Powell, three electoral votes, and what might have been | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Re-reading Clifford Stoll’s 1995 Internet predictions: Bah! | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: The Clinton interview we’d like to see | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: Recalling Dianne Feinstein’s ‘gracious tribute’ in 1995 to sex-harasser Bob Packwood | The 1995 Blog

Pingback: When the Web was new: Remembering Netscape and its fall | The 1995 Blog